Words on Spirit & Form.

David Edren has recently released a slew of collaborative projects, the latest of which sees him join forces with Bent Von Bent (Ōgon Batto) in the shape of Spirit & Form, released on Antwerp’s beloved Jj Funhouse. Here, he discusses the roots of the collaboration, his journey through experimental electronic music and the influence of gaming on his musical practice.

from an original interview by Nicholas Lewis / The Word- 19.03.20

This new album of yours, Spirit & Form, sees you join forces once again with Ōgon Batto’s Bent Von Bent. Can you talk to me about how you both met, how long you’ve been working on this specific project together as well as the synergies and similarities that led you both to make music together in the first place?

We met way back in 2006 and have since worked on quite a variety of projects together. In 2012 we started Hare Akedod, which is both a label and an audio project. I think we found ourselves having a good synergy doing things together and inspiring each other creatively. What’s more, it seems as though our collaboration also feeds both our solo output in a beneficial way as we try to review each other's work. As far as Spirit & Form goes, the project started out from the idea of trying more compositional music compared to what we were doing at the time, which was more improvisational. That’s not to say that we don’t like improvising anymore, it’s just a different idea for a different time and place - to change things around a little.

Spirit & Form is more compositional than previous releases of yours. Why were you keen for a more structured context for this album as opposed to the more improvisational tendencies you employed in previous sessions?

When I started making electronic music, I was doing a lot of sequencing, programming, sampling and stuff like that. I changed my way of working around 2006, wanting to do more organic things. Not using beats nor fixed pattern based music and try things more connected to early electronic music. This led towards all the DSR Lines output up until 2018.

You also released Tea Notes last year on Ekster together with Jatinder Singh Durhailay. Is collaborating with other artists something that comes easy to you? What are the challenges you as a musician face when in the studio with another musician?

The challenge in collaborating would of course be to find a common ground, something you both like. In all projects from the past it seems to have worked out very easily. With Tea Notes, the album also came out of improvisations which were recorded on a multi-channel and edited and mixed afterwards by myself. So I did have the most decisive role in the project. Last year, Lieven Martens and myself collaborated on a live performance and this was also a really nice Experience. Maybe one of the most free-improv things I ever did. We’d like to possibly take this further if our calendars allow it.

Meditation seems to be a recurring theme in these two

collaborations, and it is a subject I am particularly interested in, especially within the realms of experimental music. From a general perspective, do you see music - either the music you make or the music you listen to - as having any form of healing powers, and is this something you try to achieve in your own music?

For me, the simple fact of being able to take time making and listening to music is a privilege, a true luxury.

Spirit & Form’s liner notes describe the album as “an oceanic wave of sequenced sound to safeguard against the drowning of a city-stressed soul.” There is an undeniable serenity and peace of mind to the album. Can you talk to me about the recording sessions, and the frame of mind you were in whilst recording the album?

Spirit & Form’s liner notes describe the album as “an oceanic wave of sequenced sound to safeguard against the drowning of a city-stressed soul.” There is an undeniable serenity and peace of mind to the album. Can you talk to me about the recording sessions, and the frame of mind you were in whilst recording the album?The first Spirit & Form tracks materialised during a few nightly sessions in 2017, but most of the album took shape whilst we resided in a secluded house near Het Verdronken Land Van Saeftinghe, a very nice and somewhat remote nature reserve not far from Antwerp. The main reason for going there was to be able to focus on creating music and, apart from watching herons and cormorants, that’s what we did. In a way, you could say that most of the album came out of a frame of mind that was focused and relaxed, away from most urban influences.

Those same notes also talk about growing up in the 80s and 90s, and everything that comes with that. Can you talk to me about your childhood? The kind of household you grew up in? Some formative experiences, especially relating to music, that you had early on in your life?

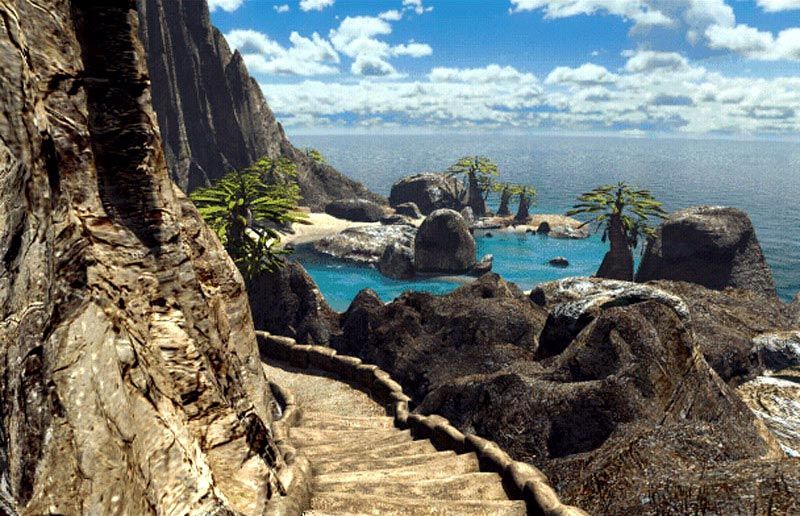

I grew up in the suburbs of Antwerp and me and my friends played outside a lot. On rainy days, we were behind CRT screens playing games on C64, Sega, Nintendo and later PC games. A lot of adventure games such as Myst, Riven and the likes but also Quake (with its Trent Reznor soundtrack) and things that spawned from that. Most of these games had amazing sounds and music, which I know certainly influenced me to make music later on. You hear artists mentioning what music inspired them, but obviously it’s more than music, it’s atmosphere and context too. We recently made a mix for Jj Funhouse’s Word radio show with things that influenced us - mostly game and film soundtracks but also some VTM station calls from the nineties.

You also released, as an add-on to the LP, an album of remixes. Pretty much the entire Antwerp scene is present, with Brussels represented too in the shape of Les Halles and Weird Dust. Why was a remix album something you were keen on doing this time around, and can you talk to me about the actual process of getting artists to rework your music? Is there a lot of back-and-forth involved, or did you employ a rather hands-off approach?

We chose specific artists we thought would fit well remixing our music. We actually only asked a very small amount of people from Antwerp, and to be honest the main goal was to ask people we feel connected to, aside from where they are based. After the album’s master was finished, the idea of a remix album formed rather quickly. The album tracks are composed with a lot of separate layers and it seemed fitting to ask people to do something with them. We restructured the channels to make it more workable and told everyone they could even use parts of a track, take it to wherever they wanted. After that, everyone just sent in a finished track. It was a rather swift undertaking to be honest.

Looking from the outside in, rituals, meditation and serenity seem to be underlying notions of interest your music draw upon. As an individual, do you have any kind of meditative practice, and if so, do they in any way shape your music?

For me making music is a meditative practice in it’s own right. Apart from that, being in or surrounded by nature is what I like to do as often as possible. Even if it’s going out for a short walk in a park or watering plants, watching birds, working with wooden or stone objects. Things like that refuel my senses.

You’ve been releasing music since the late 90s, either through your solo moniker, DSR Lines, or through other collaborative projects. Can you talk to me about the way your music might have evolved over the years? And do you see a clear difference – either in the final output or in the actual process - between your solo and collaborative works?

I try to mostly do what I like and feel and because moods change and life changes so in that respect music tends to change too. I also change setups regularly and this affects what kind of sounds you might make, what synths you might use, what sequencers you might use, etc.. Recording sounds with different gear also opens doors to other ways of working. For instance, I really enjoyed recording at Elektronmusikstudion in Stockholm where I had a residency in 2014 and 2016, it allowed me to work with the Buchla and Serge systems. At first you might try staying in your comfort zone, searching for a way to do more of what you are used to. But once you fully commit, new possibilities arise. The sounds I recorded there, and also at Worm Rotterdam, eventually made it into three or four separate albums. I do think that over the years I developed a basic way of working, recording a lot of parts and ideas and shaping and editing them into tracks that might end up on albums. I do however also believe in the value of the ‘one take’ track. Music that comes organically and does not need editing at all, straight out of an improv session or minimal focused setting.